Post-Vernacular Yiddish and Art

As I dig through contemporary Yiddish cultural creation, I find painfully little art in comparison to music and dance. A few years ago, I interviewed Los Angeles-based Barcelona-born artist Silvia Wagensberg for the Forward, who started a practice of painting Yiddish teachers, students and cultural figures. Touring through her Venice studio, I was struck by a large painting of Theo Bikel. But even more interesting was her experimental art, which struggled with the Yiddish language — sentences that she would learn and put on canvas, as imperfect as they may be.

This experimentation with calligraphy, memory and Yiddish was something I encountered a year or two ago at Culver City’s Wende Museum, which showcases art and historical exhibits that refer to the Soviet Union. The back of the museum displayed photographs of Soviet Russia by Bill Aron, and artwork by Yevgeniy Fiks.

One of Fiks’ chosen installations concerned Birobidzhan, or the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. Birobidzhan (the capital city of said region), is a city in Russia’s Far East, and was designated as a Jewish homeland in 1928. There was an organized propaganda campaign to get Jews to live in this far-flung land, which ultimately, after its heyday as a 25 percent Jewish place in 1948, is down to less than 1 percent.

Fiks, a Moscow-born artist, had heard about Birobidzhan growing up, and became fascinated by it starting in 2009. One of his projects, Landscapes of the Jewish Autonomous Zone, featured a couple of maps of the region with ‘calligraphied’ Yiddish phrases of imperfect translations of sayings in minority Russian languages.

Landscapes of the Jewish Autonomous Region, installation shot 34

2016

These pieces, from Wagensberg, who came from the perspective of her personal experience with learning Yiddish as an adult, and Fiks’, which came from absorbing the disintegration of Yiddish as a fixed national idea, represent what scholars have called “post-vernacular” Yiddish. This means the Yiddish that one uses and employs in life, in an era that no longer sees anywhere near as many native speakers as there once were.

I deeply struggle with the idea that Yiddish cannot be revived and spoken as authentically and completely as it was once lived. To me, outside of my knowledge of linguistics or sociology, this is all about justice and goodness. Yiddish being reduced to a signifier is almost like a surrender to forces benign and evil.

But this art fascinates me because it demonstrates the beauty in the struggle for Yiddish in this ‘‘post-vernacular’’ world. And it also fascinates me that it’s only through this medium that this beauty can be felt so deeply.

Fiks goes so much deeper than this in his exploration of Yiddish as a language of art and a demonstration of this struggle for self-definition and meaning. I had the pleasure of interviewing him last Sunday about his Yiddish and Birobidzhan-focused oeuvre.

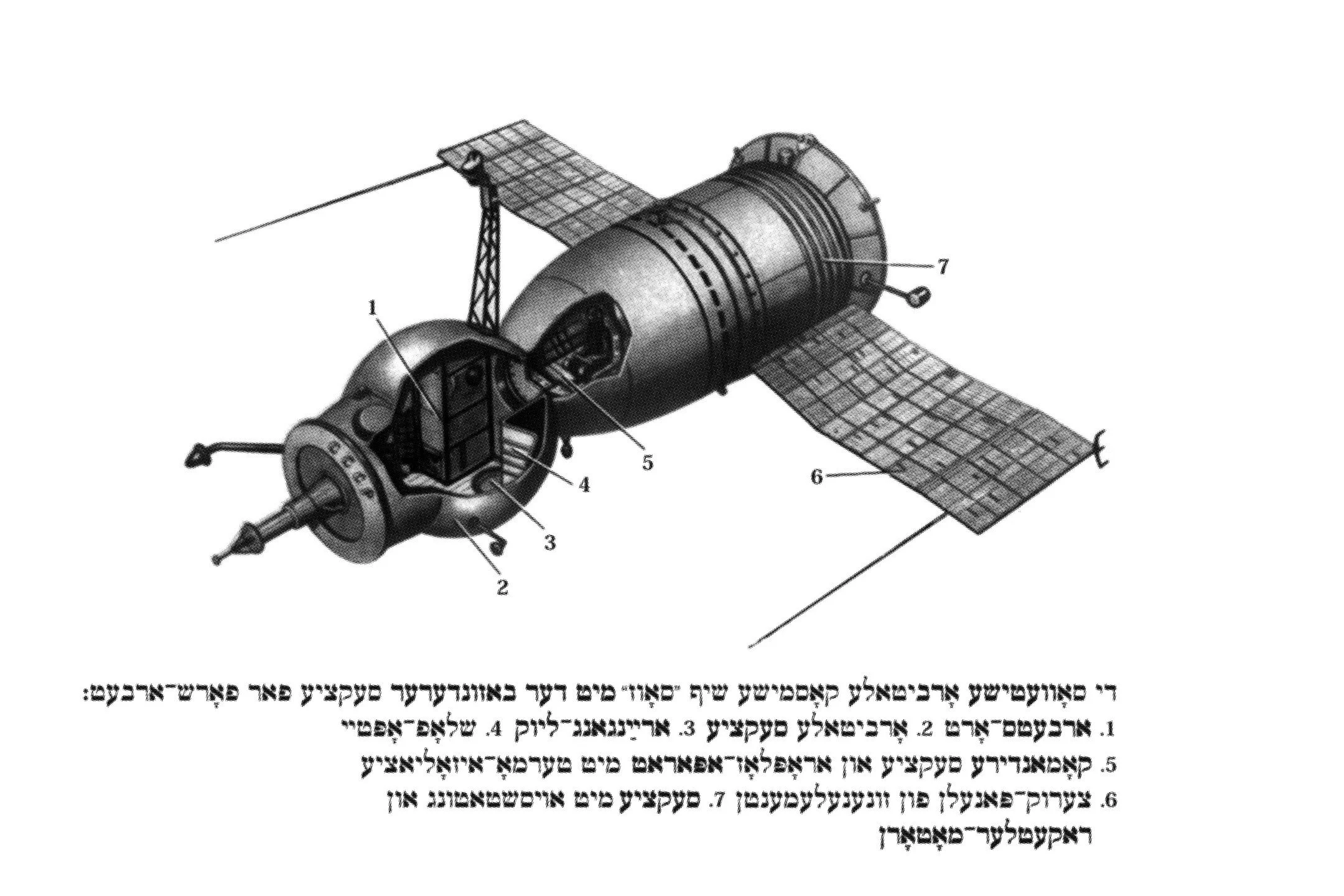

Sovetish Kosmos, Yiddish Cosmos, digital print 5

2016

Fiks was not content to have ‘‘proper’’ Yiddish in his art. He often uses whatever Yiddish he learns to translate and to write. The image above, from his exhibition on a reimagination of the Soviet space program from a Yiddish lens (based on the celebration of the Soviet space program in the magazine Sovetish Heymland), uses his own translation of a diagram of the Soyuz.

As I learned while speaking with him, it seems that much of his comfort in showcasing where he is holding in Yiddish, using it as an implicit critique of the Soviet Union and challenging understandings of nationalism, can be sourced in Fiks’ own wanderings in the world. He moved to the US several decades ago, but most cleanly finds himself at home in Yiddish, which wanders as he does, whether through exile or opportunity. His current state of existence is the lens in which he co-curated the street theater idea of the Yiddishland Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The Biennale was founded in the late 19th century to exhibition the finest art and architecture that the nations and their pavilions had to show for the world; Yiddishland Pavillion wanders on the streets and into these pavilions as a quiet but disruptive force, undermining the cleanliness of a given national expression.

While Yiddishists are often first in line to challenge borders and nationhood, their is a deeper reckoning to be had with our own imperfections in owning this language and culture which were and are ours, imperfections that come from disruptions in history that we need to encounter through the most beautiful means possible. It’s worth encountering the Yiddish-focused work of Yevgeniy Fiks to explore these ideas.