Surrealism Meets Kabbalah

Jewish mysticism is not my comfort zone, and yet because it promises to reveal secrets, a very exciting promise, it is a very popular subject. In my experience, the degree to which Jewish mystical traditions offer something of value is related to how much time one spends thinking about them. This is because they lean towards the irrational. In order to work with these ideas one has to break the hold of rationality. This is not to say that one needs to have some kind of psychotic break from reality. Rather, one needs to be able to open one’s mind to a non-rational ordering of thought. There are pictures that one looks at that are drawn in such a way that two images are present but we tend to see only one. We can teach ourselves to flip between the images with practice. So it is in accessing Jewish mysticism. With practice we can be perfectly sane and able to access the ideas in Jewish mysticism without losing ourselves.

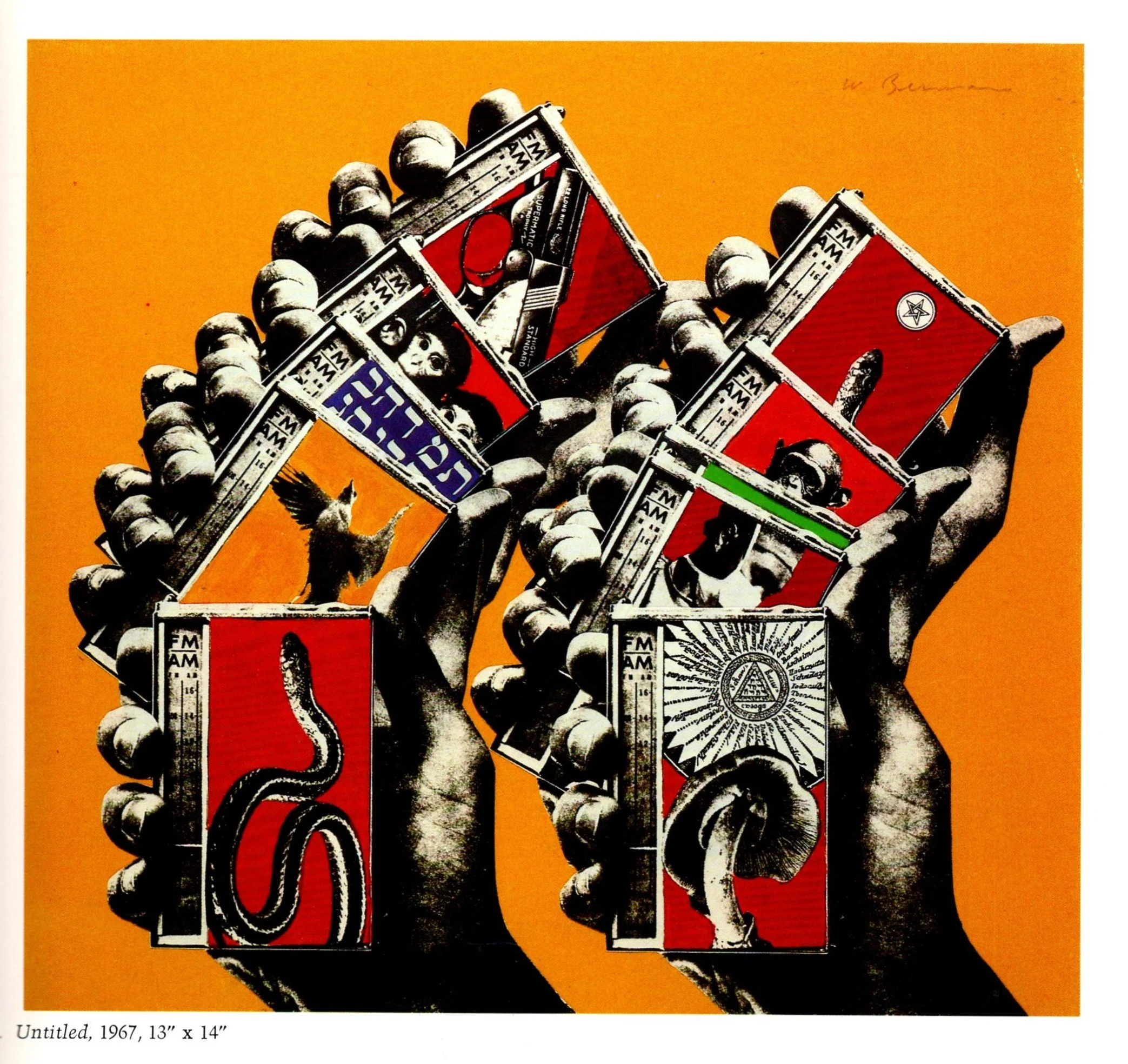

What this means in the day to day is that the signs and discourse of Jewish mysticism, as it comes up to us in popular culture, tends to move too fast for us to get much from it. This is a problem that I have had over the years in my ability to understand and accept the influence of Jewish mysticism in the work of the artist Wallace Berman. Berman’s use of the Hebrew Alphabet in his work is one of the most well-known aspects of it. His use of the Aleph is central. In his essay, “Surrealism Meets Kabbalah: Wallace Berman and the Semina Poets,” Stephen Fredman writes (weaving in quotes from Gershom Scholem and David Meltzer):

“Berman adopted another such symbol of wholeness, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, aleph, as his personal signet. Scholem points out that the aleph is a silent consonant that ‘represents nothing more than the position taken by the larynx when a word begins with a vowel.’ Aleph is the silent source of all articulation, the seed of the entire alphabet, ‘and indeed the Kabbalists regarded it as the spiritual root of all other letters.’ Berman stamped the aleph everywhere, from his motorcycle helmet to ‘Semina 7,’ entitled “ALEPH,” which is an entire issue of photography, drawings and writing by Berman dominated by the letter aleph. Speaking of Berman’’s collages and assemblages, Meltzer notes how the aleph functions in relation to the mundane imagery drawn from print sources: ‘Above the triteness and everydayness of this image continuum was Aleph – the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, which put everything into a strange tension, because on the one hand you’d see the normative images that newspapers and magazines use to increase circulation held at bay by this letter.’” [Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle].

In the essay quoted above Duncan points out that Berman grew up in the Fairfax neighborhood here in Los Angeles. He saw Hebrew letters in shop windows in the neighborhood. He didn’t receive much or any Jewish education in any organized environment, but he absorbed the sense of the Hebrew alphabet as a body of unreadable symbols which must have invested it with a kind of mystical quality. Berman came to his interest in Kabbalah through the poets Philip Lamantia and Robert Duncan, neither of whom were Jewish. Lamantia came to it through the poet Antonin Artaud who used Kabbalah as a way to help him make sense of the use of numbers in the mystical tradition of the Tarahumara Indians. He was living with them to gain access to the mystical experiences that he sought in their peyote ceremonies. Lamantia also had access to the company of the European surrealists in exile in Los Angeles in the ‘40s and ‘50s. Robert Duncan knew Kabbalah from his youth when his family attended Quaker meetings and the Kabbalah was read as a study text in the meetings.

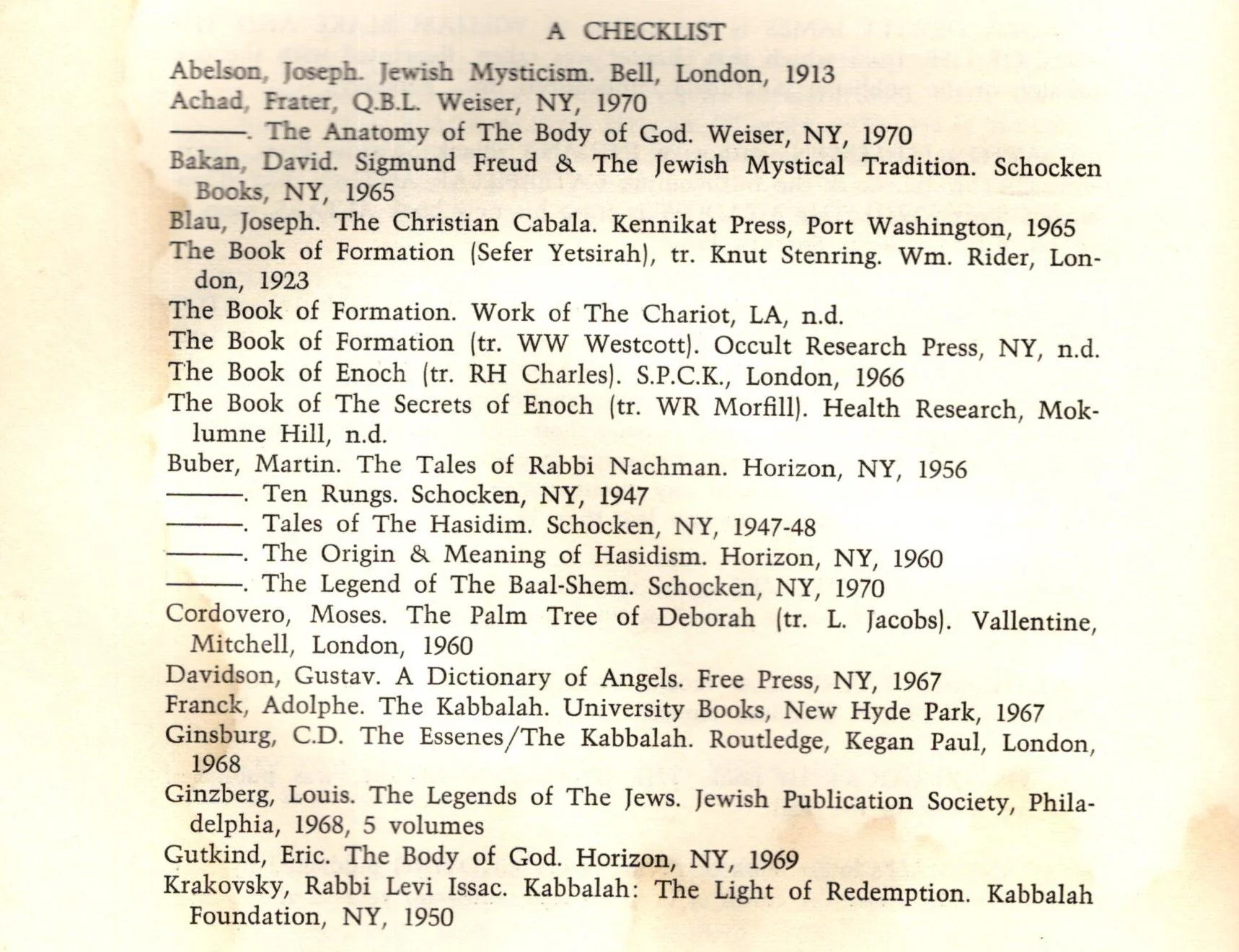

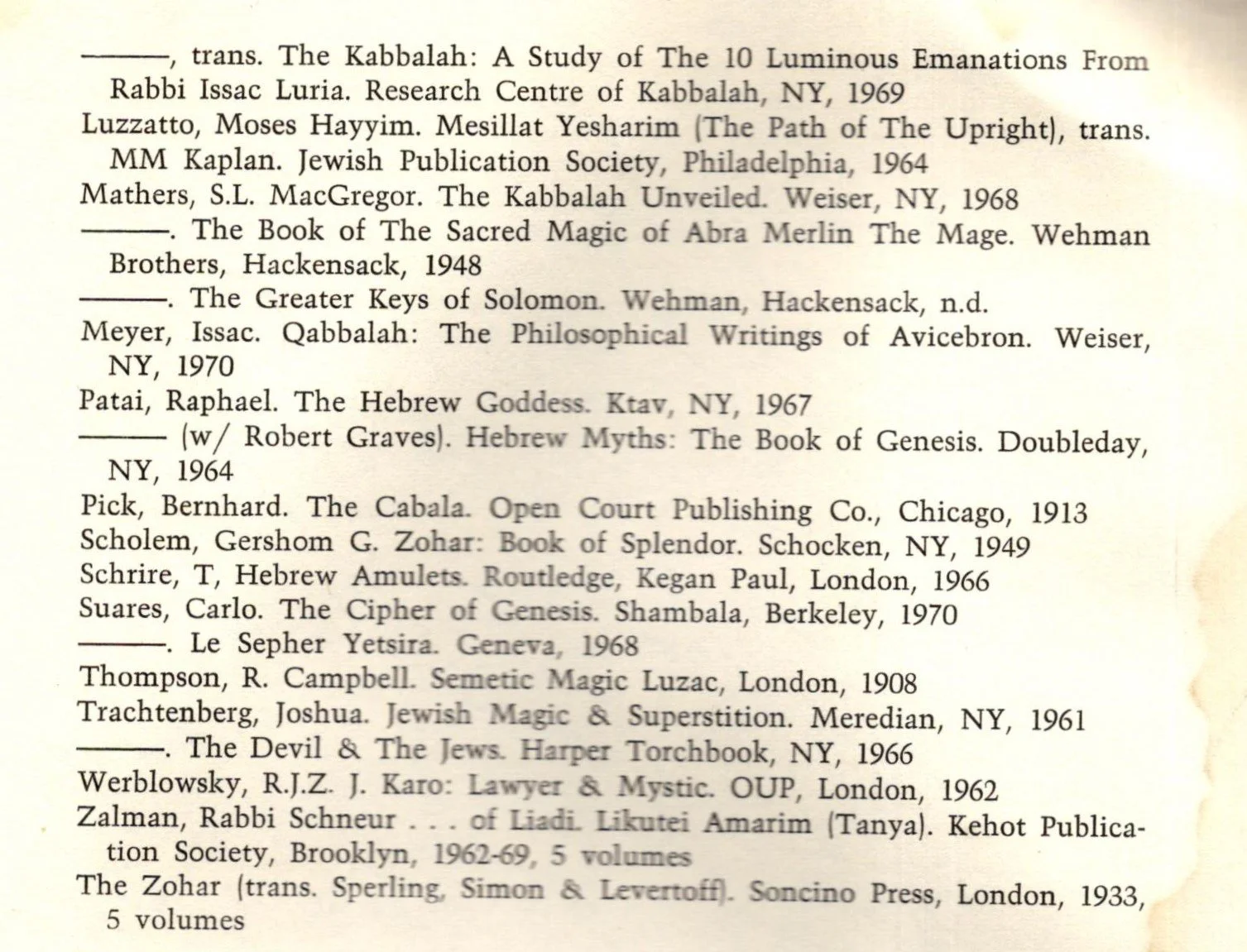

Thus, we see that Berman, the Jew, came to be introduced to Jewish mysticism by non-Jews, and the Hebrew language through books in English. At the end of the first issue of Tree, a poetry journal edited by David Meltzer [Tree: 1, Winter 1970], following a section devoted to Abraham ben Samuel Abulafia, Melzer provides “A Checklist.” It is unclear whether he wants it to be a useful bibliography for the contents of the entire issue or just the Abulafia section. [Images of this list are reproduced below.] What we see in the list is a fairly comprehensive list of the books on Jewish mysticism available in English in 1970. Along with works by Buber, Scholem, Moses Hayyim Luzzatto, Louis Ginsburg and Raphael Patai and many books published by iffier authors like Carlos Suares and S.L. Mathers. The English version of the Zohar was known to be poor. The Daniel Matt translation of the Zohar exists precisely because of how awful the earlier (and first English language) translation was. (The issue of Tree also opens with a page reproducing, on its own, Berman’s aleph).

This is the key to what was so hard for me to understand about Berman’s use of Hebrew. I read Hebrew for the meaning of the words, not the meaning of the letters as symbols on their own. In his essay on Berman in the catalog “Wallace Berman Retrospective,” David Meltzer opens with a series of quotes. From Sefer Yetsirah 2:2: “Twenty-two letters He engraved, hewed out, weighed, changed, combined, and formed out of them all existing forms, and all forms that may in the future be called into existence.” Kerith Spencer-Shapiro used this verse from Sefer Yetsirah in our meditation this week. Abulafia’s access to Jewish mystical knowledge came from his contemplation of combination of the Hebrew letters without attention to meaning and against attention to meaning. One needs to understand this to understand how Berman is using combinations of Hebrew letters.

Berman uses short combinations of Hebrew letters in his verifax collages and in some of works with accumulations of rocks painted with letters. He also did larger works on large stones and on walls with multiple lines of Hebrew letters. These larger accumulations may have Abulafia’s contemplation of the 72-letter name of God. There is only one place where Berman uses these letters to make an existing word. In the image below of a painting done on a wall we see the word Aleph-vav-taf – “Ot,” which means letter or symbol, an ironic departure from the avoidance of literal meaning.

Meltzer writes in his article mentioned above:

“In the beginning, the Judeo-Christian tradition holds sacred its origin, there was void or space or, perhaps, page. God inscribed Himself. He imprints void with Hebrew alphabet. Other texts write that God (as light, in order to see, to read) creates the universe through uttering His ineffable Name. By naming Himself, in effect, He creates the universe. Adam, in turn, recreates the world, or creates it, through language, by naming the seen and unseen.”

Meltzer also points out that in Sefer Yetsirah’s explanation of the meanings of the Hebrew letters, “Aleph is the balancing force.” (See the image below with the three robed figures with an aleph over the head of the center of the three.)

From this we can see in Berman’s use of the Hebrew letters an expression of his desire to release into the world a creative flow. Unlike biblical Adam who names what exists, Berman is trying to name what might be, to draw forth life and energy from the unrevealed potential in the world just as God had in the Divine use of the letters to create. This is a profoundly optimistic outlook.

This sense of the Hebrew letters was accessible to Berman through a translation by Gershom Scholem of a text from a student of Abulafia, who wrote:

“He used to tell me: ‘My son, it is not the intention that you come to a stop with some finite or given form, even though it be of the highest order. Much rather is this the “Path of Names”: The less understandable they are, the higher their order, until you arrive at the activity of a force which is no longer in your control, but rather your reason and your thought is in control.” … And he produced books for me made up of (combinations) of letters and names and mystic numbers (Gematrioth), of which nobody will ever be able to understand anything for they are not composed in a way meant to be understood.” [Tree:1, Scholem as translator, source not noted].

Berman seems to be trying to figure out how to rise up and take part in creation at almost a divine scale. Just as Judy Klitsner suggested about Eve in Subversive Sequels in the Bible: How Biblical Stories Mine and Undermine Each Other, Berman is seeking to match God’s creative ability. Just as God created life, Eve creates life. Just as God created an endless open and expanding system, Berman is trying to make undetermined the materials of, the seeds of, unlimited imagination.

[Note: Much of Jewish mysticism is very gendered. This is an issue that some scholars are concerned with. Gendered language can be problematic for many people. The problem with adjusting gendered language in some cases is that, where gender is an essential aspect of how the text wants to speak, adjusting the language without adjusting the ideas papers over deeper concerns. For that reason I have left all gendered language in the citations as is.]